There was civil war in England between 1135 and 1153. Henry I sought to secure the throne for his daughter, Matilda (also known as 'the Empress Maud' - her first marriage was to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry V), after his only son was killed when the "White Ship" was accidentally sunk shortly after leaving Barfleur in Normandy. Despite Henry's efforts, the throne was seized by his nephew Stephen of Blois who argued that the need to preserve order in England took priority over his earlier oaths to respect Henry I's wishes. (He also asserted that Henry changed his mind on his deathbed.)

There were few 'battles', but civil order broke down - and many of the leading nobles took steps to protect themselves. Croft and Mynard state, "fighting between the two sides was a rare event, commonly taking the form of sieges of major castles around the country." In the Milton Keynes area, at least three motte and bailey castles were quickly erected or enhanced for this purpose. There is an interesting article on motte and bailey castles here.

Wolverton Castle may have been erected by Manno [the Breton] or his son (? or possibly grandson) Meinfelin (who was to found Bradwell Priory after the Anarchy). It was held for King Stephen, and may have been destroyed as a result. The remains of a later castle may still may seen close to the church in Old Wolverton (which makes for a pleasant walk if heading towards the Iron Trunk where the canal crosses the Ouse.)

Shenley Toot is a hidden gem within Shenley Church End. It lies close to the V3 (Fulmer Street) - near a bridge by Shenley Wood Retirement Village. The remains of this motte and bailey castle lie between Oakhill Road and Holy Thorn Lane. It is under the guardianship of the Parks Trust - and there are excellent interpretation boards.

The castle belonged to (and was probably erected by) Hugh, the tenant of Earl Hugh of Chester. (also known as 'Hugh of Avranches'; Hugh the Wolf, or the less complementary 'Hugh the Fat').

Bradwell was held by William Bayeux. Croft and Mynard report that "its origins are thought to be directly related to the Anarchy". William Bayeux was the tenant of Brian Fitz Count, a personal friend of Empress Matilda. The remains lie to the north-east of the Church and south of the village hall.

A. C. Chibnall, in his 1965 book "Sherington Fiefs and Fields of a Buckinghamshire Village" suggests that there may have been similar castles at Newport Pagnell - "A mound known as 'the battery' near the confluence of [the Great Ouse and the Ouzel] marks the site of the castle and the meadow on the opposite bank of the [Ouzel] has been known since the twelfth century as 'castle mead' ... During the anarchy it belonged to Ralph Peynel as part of his barony of Dudley. Ralph held Dudley Castle for the Empress in 1137"; Lavendon and Hanslope. He proposed the following map of the castles in the north of the Milton Keynes area.

Sunday 25 June 2017

The "Anarchy"

Labels:

A. C. Chibnall,

Bradwell,

D C Mynard,

Empress Matilda,

Henry I,

King Stephen,

Manno the Breton,

Meinfelin,

R A Croft,

Shenley Church End,

Shenley Toot,

The Anarchy,

Wolverton

Location:

Furzton, Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Sunday 18 June 2017

The Doomsday Book

At a meeting of his Court in Gloucester at Christmas 1085, William the Conqueror ordered that a survey be undertaken of the country. He wanted to find out ''How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire.'' He wanted to know the potential for taxing the inhabitants of the land that he had conquered.

Places in today's Milton Keynes are recorded in the survey - which was completed within a year. Sir Frank Markham's "History of Milton Keynes and District" Volume 1 lists them in his chapter on The Normans.

There is also book available which contains the results of the survey for Buckinghamshire. It is the "Doomsday Book: Buckinghamshire" volume in a series "History from the Sources", edited by John Morris, published by Phillimore. I bought both books in Central Milton Keynes.

The survey lists the owners of land. They may have derived an income from their land, but possibly never visited. All land was the King's, but he gave an interest in the land to his "tenants", they in turn gave lesser interests to other people. The Doomsday Book records entries - as for Hugh of Bolbec

"[In Seckloe Hundred] - In (Great) Linford - Hugh holds 2 hides and 1.5 virgates as one manor. Land for 2 ploughs; in Lordship 1. 5 villagers with 2 smallholders have 1 plough. Meadow there for 1 plough. The value is and was 20s; before 1066, 40s. Three thanes held the manor; they could grant and sell."

or for the Bishop of Bayeux

"[in Moulsoe Hundred] - In (Little) Brickhill Thurstan holds 1 hide from the Bishop. Land for 1 plough, but there is no plough there, only 3 villagers with 2 smallholders. The value is and was 14s; before 1066, 20s. Alwin, Estan's man, held this manor; he could not grant or sell outside Brickhill, Estan's manor."

(translations from "History from the Sources: Doomsday Book: Buckinghamshire - ed. John Morris)

A "Hide" was a unit of measurement designed originally to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household. Although sometimes described as being 120 acres (49 hectares), it varied according to the nature of the land. One source says that "there was a tendency for land producing £1 of income per year to be assessed at 1 hide." A virgate was usually, but not always considered as a quarter of a hide.

The survey, undertaken 20 years after William led the invasion from Normandy, shows evidence that "to the victor go the spoils". The following list show where particular people had holdings, it is not signify that they held the whole of the property in that village. {Note - this is NOT an exhaustive list]

William's half brothers head our list -

Odo of Bayeux (Earl of Kent and Bishop of Bayeux)

- Little Brickhill

Robert, Count of Mortain

- Caldecote

- Lavendon

- Loughton

- Great Linford

- Wavendon

- Weston Underwood

- Woughton

Other Landholders included

Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances

- Clifton Reyes

- Emberton

- Lathbury

- Lavendon

- Little Linford

- Olney

- Sherington

- Simpson

- Stoke Goldington

- Tyringham

- Water Eaton

- Weston Underwood

Earl Hugh of Chester

- Shenley Church End

- Great Brickhill

Richard Ingania (the Artificer)

- Shenley Brook End

Urso of Bercheres

- Shenley Brook End

Gilbert Maminot, Bishop of Lisieux

- Brickhill

William, son of Ansculf

- Bradwell

- Caldecote

- Chicheley

- Great Linford

- Hardmead

- Little Woolstone

- Milton Keynes

- Newport Pagnell

- Tickford

- Tyringham

Hugh of Bolbec

- Calverton

- Great Linford

- Hardmead

- Wavendon

Mainou (Manno) the Breton

- Loughton

- Stoke Hammond

- Wolverton (can I recommend Bryan Dunleavy's excellent book - Manno's Manor: A History of Wolverton)

Places in today's Milton Keynes are recorded in the survey - which was completed within a year. Sir Frank Markham's "History of Milton Keynes and District" Volume 1 lists them in his chapter on The Normans.

There is also book available which contains the results of the survey for Buckinghamshire. It is the "Doomsday Book: Buckinghamshire" volume in a series "History from the Sources", edited by John Morris, published by Phillimore. I bought both books in Central Milton Keynes.

The survey lists the owners of land. They may have derived an income from their land, but possibly never visited. All land was the King's, but he gave an interest in the land to his "tenants", they in turn gave lesser interests to other people. The Doomsday Book records entries - as for Hugh of Bolbec

"[In Seckloe Hundred] - In (Great) Linford - Hugh holds 2 hides and 1.5 virgates as one manor. Land for 2 ploughs; in Lordship 1. 5 villagers with 2 smallholders have 1 plough. Meadow there for 1 plough. The value is and was 20s; before 1066, 40s. Three thanes held the manor; they could grant and sell."

or for the Bishop of Bayeux

"[in Moulsoe Hundred] - In (Little) Brickhill Thurstan holds 1 hide from the Bishop. Land for 1 plough, but there is no plough there, only 3 villagers with 2 smallholders. The value is and was 14s; before 1066, 20s. Alwin, Estan's man, held this manor; he could not grant or sell outside Brickhill, Estan's manor."

(translations from "History from the Sources: Doomsday Book: Buckinghamshire - ed. John Morris)

A "Hide" was a unit of measurement designed originally to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household. Although sometimes described as being 120 acres (49 hectares), it varied according to the nature of the land. One source says that "there was a tendency for land producing £1 of income per year to be assessed at 1 hide." A virgate was usually, but not always considered as a quarter of a hide.

The survey, undertaken 20 years after William led the invasion from Normandy, shows evidence that "to the victor go the spoils". The following list show where particular people had holdings, it is not signify that they held the whole of the property in that village. {Note - this is NOT an exhaustive list]

William's half brothers head our list -

Odo of Bayeux (Earl of Kent and Bishop of Bayeux)

- Little Brickhill

Robert, Count of Mortain

- Caldecote

- Lavendon

- Loughton

- Great Linford

- Wavendon

- Weston Underwood

- Woughton

Other Landholders included

Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances

- Clifton Reyes

- Emberton

- Lathbury

- Lavendon

- Little Linford

- Olney

- Sherington

- Simpson

- Stoke Goldington

- Tyringham

- Water Eaton

- Weston Underwood

Earl Hugh of Chester

- Shenley Church End

- Great Brickhill

Richard Ingania (the Artificer)

- Shenley Brook End

Urso of Bercheres

- Shenley Brook End

Gilbert Maminot, Bishop of Lisieux

- Brickhill

William, son of Ansculf

- Bradwell

- Caldecote

- Chicheley

- Great Linford

- Hardmead

- Little Woolstone

- Milton Keynes

- Newport Pagnell

- Tickford

- Tyringham

Hugh of Bolbec

- Calverton

- Great Linford

- Hardmead

- Wavendon

Mainou (Manno) the Breton

- Loughton

- Stoke Hammond

- Wolverton (can I recommend Bryan Dunleavy's excellent book - Manno's Manor: A History of Wolverton)

Thursday 15 June 2017

Magna Carta Day

802 years ago, King John was forced to do a deal with rebel barons on the meadows of Runnymede. They had become exasperated with his abuse of executive power - and demanded a halt.

I|n doing so they forced him to concede a principle which is central to the modern British Constitution - that the Executive must operate within the bounds of its legal authority.

It was a start - and although John sought to renege on it (and provoked a civil war which ended with his death)"., the principle remains. It has been developed further.But today we can rightly celebrate what happened on those Surrey meadows over eight centuries ago.

I|n doing so they forced him to concede a principle which is central to the modern British Constitution - that the Executive must operate within the bounds of its legal authority.

It was a start - and although John sought to renege on it (and provoked a civil war which ended with his death)"., the principle remains. It has been developed further.But today we can rightly celebrate what happened on those Surrey meadows over eight centuries ago.

Labels:

Magna Carta,

Rule of Law,

Runnymede

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Monday 29 May 2017

William the Marshal

BBC Four showed an excellent documentary called "The Greatest Knight: William the Marshal". Some of its topics are close to some topics highlighted on this blog.

It discusses "the anarchy" - the civil war period (1135-53) during the reign of King Stephen. In the series on Milton Keynes history, we will shortly be looking at the remains of that conflict in Shenley, Bradwell and Wolverton.

It also focuses on William's role in the granting of the Magna Carta - a subject that this blog will focus on during June.

In addition it references Eleanor of Aquitaine's court in Poitiers - the remains of which are incorporated in the Palais de Justice, a place I have visited (and hope to do so again). William was also present at the burial of Henry II in Fontevraud Abbey (another of my favorite places). He later lived in Chepstow Castle - a castle I frequently visited as a child.

If you are able to access the BBC iPlayer (only available to TV licence holders in the UK) - I can happily recommend this programme.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03z2l6l

Labels:

1st Earl of Pembroke,

BBC Four,

Bradwell,

Chepstow Castle,

Eleanor of Aquitaine,

Fontevraud Abbey,

Shenley Church End,

William the Marshal,

Wolverton

Location:

Furzton, Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Wednesday 24 May 2017

Was our area ravaged in 1066?

I've recently been reading the Osprey Guide to the Campaigns of the Norman Conquest by Matthew Bennett. In a map entitled "William's march to London, October - December 1066" it shows the routes, both of William the Conqueror himself - as he skirted around London; crossing the Thames to Wallingford - and along the Chilterns to Berkhamsted. (see my earlier posts on Berkhamsted - here and here)

and the route taken by a "detachment for ravaging" - This group, according to that map left from Wallingford and headed for Buckingham and Stony Stratford, and then on to Bedford. it identifies the area south of the Great Ouse as "lands severely ravaged". The Milton Keynes area east of Watling street is included in this area.

There are no diaries or other accounts which discuss this, so where is the evidence? The theory is based on a study of the Domesday Book - which looks at the change in the value of land between the start of 1066 and in 1070 and 1086. Milton Keynes, the village was worth £8 in 1066, but dropped to £5 by 1070 - Great Linford fell in value from £4 in 1066 to £2 in 1070, then increased to £3 by 1086. Newport Pagnell fell from £24 to £20. It is suggested that these drops in value reflected a ravaging of the area. Whaddon and Newton Longville kept their value.

An interesting theory? But is it correct - did much of our area suffer a long term decline as a result of the aggressive tactics of Norman soldiers?

and the route taken by a "detachment for ravaging" - This group, according to that map left from Wallingford and headed for Buckingham and Stony Stratford, and then on to Bedford. it identifies the area south of the Great Ouse as "lands severely ravaged". The Milton Keynes area east of Watling street is included in this area.

There are no diaries or other accounts which discuss this, so where is the evidence? The theory is based on a study of the Domesday Book - which looks at the change in the value of land between the start of 1066 and in 1070 and 1086. Milton Keynes, the village was worth £8 in 1066, but dropped to £5 by 1070 - Great Linford fell in value from £4 in 1066 to £2 in 1070, then increased to £3 by 1086. Newport Pagnell fell from £24 to £20. It is suggested that these drops in value reflected a ravaging of the area. Whaddon and Newton Longville kept their value.

An interesting theory? But is it correct - did much of our area suffer a long term decline as a result of the aggressive tactics of Norman soldiers?

Labels:

Berkhamsted,

Great Linford,

Matthew Bennett,

Milton Keynes village,

Newport Pagnell,

Newton Longville,

Wallingford,

Whaddon,

William the Conqueror

Location:

Furzton, Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Saturday 20 May 2017

Border Country

Milton Keynes is now a peaceable part of a United Kingdom. But it has not always been that way (in a future post I will look at the motte and bailey castles put up in Shenley, Bradwell and Wolverton at the time of "the anarchy" during King Stephen's reign)

At school, I was taught that the Anglo-Saxon kingdom was divided from a Viking kingdom (known as the 'Danelaw') by Watling Street.

In fact this border ran across the country using the old Roman road - until it came to the crossing of the Great Ouse - where Watling Street ran through Old Stratford into Stony Stratford. At that point the boundary follows the Great Ouse to Bedford. It then went directly south to the source of the River Lea and followed that to the Thames.

A Treaty between King Alfred of Wessex (see http://jdmhistory.blogspot.co.uk/2017/04/alfred-great.html) and Guthrum, the leader of a Viking force that had invaded in 874 and brought Wessex to the point of extinction in 878, and then became the ruler of East Anglia - was agreed at some point between 878 and 890.

At school, I was taught that the Anglo-Saxon kingdom was divided from a Viking kingdom (known as the 'Danelaw') by Watling Street.

In fact this border ran across the country using the old Roman road - until it came to the crossing of the Great Ouse - where Watling Street ran through Old Stratford into Stony Stratford. At that point the boundary follows the Great Ouse to Bedford. It then went directly south to the source of the River Lea and followed that to the Thames.

A Treaty between King Alfred of Wessex (see http://jdmhistory.blogspot.co.uk/2017/04/alfred-great.html) and Guthrum, the leader of a Viking force that had invaded in 874 and brought Wessex to the point of extinction in 878, and then became the ruler of East Anglia - was agreed at some point between 878 and 890.

Saturday 29 April 2017

History of the House of Lords

I have a keen interest in the history of Parliament. I hope in the future to write a number of short posts about the history of that institution - and some of the extraordinary events associated with it.

In the meantime - there is an excellent brief summary of the history of the House of Lords available to download - for free! from -

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/LLN-2017-0020

In the meantime - there is an excellent brief summary of the history of the House of Lords available to download - for free! from -

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/LLN-2017-0020

Labels:

House of Lords,

Parliament

Location:

Milton Keynes, UK

Monday 24 April 2017

Forthcoming Posts

The pace of posts may drop in the coming few weeks. There's an election on - and that means I have less time to research and post - but do subscribe, or return occasionally - I hope to get some time for the research and writing that I enjoy.

Saturday 22 April 2017

Alfred the Great

Most of our Monarchs are known by their number, but only Alfred is popularly known as 'the Great'. (Sometimes Cnut [Canute] is also described by the title). He was a remarkable, and unusual King. The Victorians stressed his role as a warrior, but he was a learned man - dedicated to promoting education. Whilst King of Wessex, he is remembered as an essentially English King. Yet he had a very European outlook - and had visited Rome and the court of Charles the Bald, King of the Franks. He encouraged scholars from across the continent. His step-mother was the daughter of Charles.

Many books have been written about him. The first - and a major source for later writers was written by Bishop Asser, who spent time at Alfred's Court. I very much enjoyed reading David Horspool's book.

The tale of the burning of the cakes, sadly, has no basis in fact. What we do know is that he was born in Wantage in 848 or 849. He was the youngest of five sons and a daughter of Aethelwulf, King of the West Saxons (reigned 839-858) and the grandson of King Egbert, whose defeat of the Mercians in 825, brought an end to their domination of England - and the establishment of Wessex as the greatest (and ultimately only remaining) kingdom of England. All of Alfred's brothers preceded him as King.

Alfred's reign was dominated by the struggle with the Vikings. Raids by these sea-faring folk from Scandinavia began in 789, but Alfred faced invasion. Most of England succumbed to the invaders, and at a low point in his reign, Alfred fled to Athelney, an island in the 'very great swampy and impassable marshes' of the Somerset Levels. From there he launched the fightback - eventually forcing the invaders out of his kingdom and liberating London. He re-established the city within its original walls.

He was a reformer in many fields. He reorganised the defences of the country, establishing a series of burhs (boroughs) across the south of England. These fortified towns were key to his military success.

A BBC webpage describes his other great contributions - "As an administrator Alfred advocated justice and order and established a code of laws and a reformed coinage. He had a strong belief in the importance of education and learnt Latin in his late thirties. He then arranged, and himself took part in, the translation of books from Latin to Anglo-Saxon."

His main capital was at Winchester, where he died in 899 - and was buried firstly in the old Minister, then ultimately in Hyde Abbey.

Wednesday 19 April 2017

Milton Keynes in the Ice Age

I popped into the Central Library in Milton Keynes today (to check that I was on the Electoral Register) - and noticed an advertisement for an exhibition about the Ice Age in the MK area. It is being held in the Exhibition area (downstairs, behind the service desks - where the local studies section of the library used to be).

It was an interesting exhibition - explaining the geological research that led to the identification of the ice ages in Britain (there were a number - and the term can apply to a specific period - or to the general period which saw both warm and cold periods). There were also exhibits of animal remains from the creatures who were resident in this area. Good interpretation boards explained the different human species around.

I liked the way that local finds were highlighted (even if they weren't actually on display themselves.)

Well worth a visit - it's on until 11th May.

It was an interesting exhibition - explaining the geological research that led to the identification of the ice ages in Britain (there were a number - and the term can apply to a specific period - or to the general period which saw both warm and cold periods). There were also exhibits of animal remains from the creatures who were resident in this area. Good interpretation boards explained the different human species around.

I liked the way that local finds were highlighted (even if they weren't actually on display themselves.)

Well worth a visit - it's on until 11th May.

Labels:

Central Library,

Iron Age,

Milton Keynes

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Tuesday 18 April 2017

Secklow Mound

Just behind the Central Library in Milton Keynes, a low mound stands. It has recently been given a new interpretation board, explaining the history and significance of the site.

'Hundreds' were an important part of the hierarchy within England for over a thousand years. Beneath the 'Kingdom' were 'counties'. These were divided into 'hundreds', which themselves were made up of a number of parishes. In the Milton Keynes area the main 'hundred' was called Secklow. However, not all parishes covered by the modern city were in the Secklow Hundred. I live in Furzton, which was part of Shenley Brook End parish - which was in the Mursley Hundred (which extended to Winslow and Stewkley). Bunsty Hundred covered Haversham and Hanslope across to Olney and Lavenham. Moulsoe Hundred included the Brickhills, Wavendon, Milton Keynes Village, Broughton and up to Clifton Keynes.

A 'Hundred' was supposed to include 100 'hides'. One hide was regarded as the amount of land required to support one family group. In practice the size of hundreds varied significantly. Each Hundred had its own 'folk moot' - a meeting of the people within the Hundred to discuss local issues and to ensure that justice was meted out to law-breakers. Sadly, they weren't as democratic as they sound, often being limited to significant land-holders.

The Secklow mound was the meeting place for the 'folk-moot' of the Secklow (or 'Seckley') Hundred. The full list of parishes within the Hundred are listed in http://opendomesday.org/hundred/seckley/ (which also gives the information recorded about them in the Doomsday Book). It covered the area from Water Eaton and Shenley Church End to Stony Stratford and westwards towards Newport Pagnell and Simpson.

'Hundreds' were an important part of the hierarchy within England for over a thousand years. Beneath the 'Kingdom' were 'counties'. These were divided into 'hundreds', which themselves were made up of a number of parishes. In the Milton Keynes area the main 'hundred' was called Secklow. However, not all parishes covered by the modern city were in the Secklow Hundred. I live in Furzton, which was part of Shenley Brook End parish - which was in the Mursley Hundred (which extended to Winslow and Stewkley). Bunsty Hundred covered Haversham and Hanslope across to Olney and Lavenham. Moulsoe Hundred included the Brickhills, Wavendon, Milton Keynes Village, Broughton and up to Clifton Keynes.

A 'Hundred' was supposed to include 100 'hides'. One hide was regarded as the amount of land required to support one family group. In practice the size of hundreds varied significantly. Each Hundred had its own 'folk moot' - a meeting of the people within the Hundred to discuss local issues and to ensure that justice was meted out to law-breakers. Sadly, they weren't as democratic as they sound, often being limited to significant land-holders.

The Secklow mound was the meeting place for the 'folk-moot' of the Secklow (or 'Seckley') Hundred. The full list of parishes within the Hundred are listed in http://opendomesday.org/hundred/seckley/ (which also gives the information recorded about them in the Doomsday Book). It covered the area from Water Eaton and Shenley Church End to Stony Stratford and westwards towards Newport Pagnell and Simpson.

Labels:

Bunsty Hundred,

Doomsday Book,

Folk Moot,

Furzton,

Milton Keynes village,

Moulsoe Hundred,

Mursley Hundred,

Newport Pagnell,

Secklow Hundred,

Secklow Mound,

Shenley Brook End,

Shenley Church End,

Water Eaton

Location:

Furzton, Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Sunday 16 April 2017

The Saxons in Milton Keynes

Does history repeat itself?

In 409 AD the British "revolted from the Roman Empire, 'rejected Roman law, reverted to their native customs, and armed themselves to ensure their own safety'" - an early Brexit? The following year (410 AD) "Emperor Honorius sends his Rescript (diplomatic letters) to the Romano-British magistrates, where he explains that the cities in Britain must provide for their own defence against the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons. This effectively ends Roman rule in Great Britain."

410 CE/AD is often described as the last year of Roman Britain, the year we entered the "Anglo-Saxon period". In fact things didn't change overnight. As with the start of the Roman era, settlement patterns and daily life evolved more slowly.

Croft and Mynard commented in their excellent book 'The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes' - "It is clear that settlement of the area in the Roman period was extensive, so it is likely that any Saxon people entering the area would have found the remains of a well-managed agrarian landscape...It is likely that rough pasture, scrubland and even woodland had regenerated over some of the former arable lands of the villa estates. The place-name evidence in the Shenley (Bright clearing) and Bletchley (Blaecc's clearing) areas tends to confirm the wooded nature of these areas in the 7th and 8th centuries."

The map of the area did change. Magiovinium, Bancroft and other roman sites were abandoned, whilst other areas saw new development. Even places like Pennyland and the Hartigans gravel pit (near Milton Keynes village), which had seen earlier settlements abandoned in the early Roman period, saw new settlements develop. While Bancroft villa was left to decay, settlement on the hill at Blue Bridge revived.

The Saxons originated mainly in the area we know today as northern Germany and Denmark. At first they were sea-borne raiders - but in the turbulence of the collapse of the Roman Empire they began to settle. Saxon sites have been discovered in Old Wolverton, Westbury (actually in what we now call Shenley Brook End), Pennyland and Newport Pagnell. As noted above, some of our City's place names have Saxon origins. Michael Farley in his 'Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire' claims that "by AD 500 it is fairly likely that Buckinghamshire was to all intents and purposes a Saxon county...lacking documentation it is too early to know which principle tribal grouping (e.g. Anglian, West Saxon, etc) was dominant here." We know that they arrived holding pagan beliefs, but Christianity re-established itself during the early Saxon period. The most complete Saxon church in Buckinghamshire is to be found in Wing, between Milton Keynes and Aylesbury.

It is during the Saxon period that the "hundreds" were established. In a forthcoming post I will describe the Secklow Mound, which lies behind the Central Library in Milton Keynes.

In 409 AD the British "revolted from the Roman Empire, 'rejected Roman law, reverted to their native customs, and armed themselves to ensure their own safety'" - an early Brexit? The following year (410 AD) "Emperor Honorius sends his Rescript (diplomatic letters) to the Romano-British magistrates, where he explains that the cities in Britain must provide for their own defence against the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons. This effectively ends Roman rule in Great Britain."

410 CE/AD is often described as the last year of Roman Britain, the year we entered the "Anglo-Saxon period". In fact things didn't change overnight. As with the start of the Roman era, settlement patterns and daily life evolved more slowly.

Croft and Mynard commented in their excellent book 'The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes' - "It is clear that settlement of the area in the Roman period was extensive, so it is likely that any Saxon people entering the area would have found the remains of a well-managed agrarian landscape...It is likely that rough pasture, scrubland and even woodland had regenerated over some of the former arable lands of the villa estates. The place-name evidence in the Shenley (Bright clearing) and Bletchley (Blaecc's clearing) areas tends to confirm the wooded nature of these areas in the 7th and 8th centuries."

The map of the area did change. Magiovinium, Bancroft and other roman sites were abandoned, whilst other areas saw new development. Even places like Pennyland and the Hartigans gravel pit (near Milton Keynes village), which had seen earlier settlements abandoned in the early Roman period, saw new settlements develop. While Bancroft villa was left to decay, settlement on the hill at Blue Bridge revived.

The Saxons originated mainly in the area we know today as northern Germany and Denmark. At first they were sea-borne raiders - but in the turbulence of the collapse of the Roman Empire they began to settle. Saxon sites have been discovered in Old Wolverton, Westbury (actually in what we now call Shenley Brook End), Pennyland and Newport Pagnell. As noted above, some of our City's place names have Saxon origins. Michael Farley in his 'Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire' claims that "by AD 500 it is fairly likely that Buckinghamshire was to all intents and purposes a Saxon county...lacking documentation it is too early to know which principle tribal grouping (e.g. Anglian, West Saxon, etc) was dominant here." We know that they arrived holding pagan beliefs, but Christianity re-established itself during the early Saxon period. The most complete Saxon church in Buckinghamshire is to be found in Wing, between Milton Keynes and Aylesbury.

It is during the Saxon period that the "hundreds" were established. In a forthcoming post I will describe the Secklow Mound, which lies behind the Central Library in Milton Keynes.

Labels:

Bancroft Roman Villa,

Bletchley,

Blue Bridge,

Brexit,

D C Mynard,

M. Farley,

Magiovinium,

Newport Pagnell,

Pennyland,

R A Croft,

Saxons,

Secklow Mound,

Shenley,

Shenley Brook End,

Wing

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Thursday 13 April 2017

Thornborough

The Bletchley to Buckingham road (A421) has long been recognised as a roman road. Shortly before arriving at the outskirts of Buckingham there is a lay-by which was once the main route. There's a lovely ancient bridge, the only surviving medieval bridge in Buckinghamshire, which dates from the fourteenth century - and in the fields nearby there are two Roman barrows.

It is believed that five roman roads met at Thornborough. The remains of the roman village is now protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 (as amended) as it appears to the Secretary of State to be of national importance. The barrows were first excavated by the Duke of Buckingham in 1839. Remains of high status romans and their possessions were found, along with evidence of later burials from the anglo-saxon period. The description by Historic England states...

"The western barrow is roughly circular in plan, measuring c.40m in diameter and 3.5m high, with steep sides leading to a flattened area on the summit some 15m across. Slight traces of the ditch surrounding the mound remain visible around the south western side.

The second barrow lies about 30m to the east. It is similar in size to the western barrow, although slightly more oval in appearance, and appears marginally higher due to its position on the hillside.

Traces of the encircling ditch are also visible around the east and west sides of the mound... One (although it is not recorded which) proved to have been previously robbed and little was recovered. The other revealed a floor of rough limestone blocks which had stood beneath a timber structure, some of the oak timbers of which survived intact. Within this area were found three bronze jugs; a bronze lamp and a patera (a shallow, circular dish); a cup, bowl and platter of samian-ware (red pottery imported from Gaul); two ceramic storage jars (or amphorae); a small lozenge-shaped piece of gold, and two glass vessels, the larger of which contained the cremated remains of the deceased. The calcined condition of the limestone pavement indicated that it had been used as the base of the funeral pyre.

Traces of iron objects were noted at the time, but these apparently did not survive the excavation. The remaining finds, with the exception of the gold object, were later purchased by the local antiquarian R C Neville (fourth Lord Braybrooke) and are now held by the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. They date from the first and second centuries AD (some being old when buried, perhaps being retained for generations as family heirlooms) and demonstrate that one of the barrows was constructed in the late second century AD. The other is thought to be of the same date."

It is believed that five roman roads met at Thornborough. The remains of the roman village is now protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 (as amended) as it appears to the Secretary of State to be of national importance. The barrows were first excavated by the Duke of Buckingham in 1839. Remains of high status romans and their possessions were found, along with evidence of later burials from the anglo-saxon period. The description by Historic England states...

"The western barrow is roughly circular in plan, measuring c.40m in diameter and 3.5m high, with steep sides leading to a flattened area on the summit some 15m across. Slight traces of the ditch surrounding the mound remain visible around the south western side.

The second barrow lies about 30m to the east. It is similar in size to the western barrow, although slightly more oval in appearance, and appears marginally higher due to its position on the hillside.

Traces of the encircling ditch are also visible around the east and west sides of the mound... One (although it is not recorded which) proved to have been previously robbed and little was recovered. The other revealed a floor of rough limestone blocks which had stood beneath a timber structure, some of the oak timbers of which survived intact. Within this area were found three bronze jugs; a bronze lamp and a patera (a shallow, circular dish); a cup, bowl and platter of samian-ware (red pottery imported from Gaul); two ceramic storage jars (or amphorae); a small lozenge-shaped piece of gold, and two glass vessels, the larger of which contained the cremated remains of the deceased. The calcined condition of the limestone pavement indicated that it had been used as the base of the funeral pyre.

Traces of iron objects were noted at the time, but these apparently did not survive the excavation. The remaining finds, with the exception of the gold object, were later purchased by the local antiquarian R C Neville (fourth Lord Braybrooke) and are now held by the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. They date from the first and second centuries AD (some being old when buried, perhaps being retained for generations as family heirlooms) and demonstrate that one of the barrows was constructed in the late second century AD. The other is thought to be of the same date."

One article I read had the worrying title - "ISIS AT THORNBOROUGH" - which today has a meaning very different from the one intended when the article was written. This article - available at http://www.bucksas.org.uk/rob/rob_25_0_139.pdf - describes the rare bronze figurine of the goddess "Isis", an Egyptian goddess - often identified with Fortuna in Greek and Roman contexts.

The Historic England description of the site can be accessed here.

Saturday 8 April 2017

The Roman Roads of Milton Keynes

Watling Street is the name given later for the major Roman road (which may actually follow a more ancient route) which ran from the ports in Kent (Dubris (Dover) and Rutupiae (Richborough)), via Londinium (London), Verulamium (St Albans) onto Viroconium (Wroxeter). It then splits, continuing what may be more ancient routes towards Holyhead and Deva (Chester). The Antonine Itinerary, Route II extends the route beyond Deva to Hadrian's Wall.

In Milton Keynes, it enters the current boundary of the Unitary Authority at the roundabout on the A5 trunk route where it meets A4146. It runs through Fenny Stratford to the 'Roman' roundabouts near the Bletchley Tesco. It runs alongside Bletcham Way and the start of the V4 near the MK Dons Stadium, on Denbigh Road. It then follows the V4, which diverts to avoid the original route of Watling Street through Loughton and Stony Stratford. In Stony Stratford, Watling Street is the London Road and High Street. Watling Street exits Milton Keynes as it crosses the Great Ouse.

On its route it crosses a number of streams and the Great Ouse on bridges, but these were probably fords in Roman times.

There were other Roman roads in the area. The Bletchley to Buckingham road is believed to be of at least Roman foundation.

"Viatores" is the name used by a number of scholars who published a book in 1964 which sought to identify possible Roman roads in the South East Midlands. Some of these roads are definitely Roman - but others are conjectures based upon known settlements, parish boundaries and previous archaeological finds. I'm not in a position to evaluate how much of work has been proven by later research - but the book is a useful starting point.

MKi Observatory used to have a Heritage Theme which showed the Viatores routes relative to the modern roads and paths. I have not been able to find it recently, but if anyone can provide a link - please share it with me. I do recall that one route crossed the southern end of Milton Keynes Central railway station, crossing Loughton towards Shenley Brook End near to the current route of Child's Way. The picture below shows the Viatores routes in the general area.

In Milton Keynes, it enters the current boundary of the Unitary Authority at the roundabout on the A5 trunk route where it meets A4146. It runs through Fenny Stratford to the 'Roman' roundabouts near the Bletchley Tesco. It runs alongside Bletcham Way and the start of the V4 near the MK Dons Stadium, on Denbigh Road. It then follows the V4, which diverts to avoid the original route of Watling Street through Loughton and Stony Stratford. In Stony Stratford, Watling Street is the London Road and High Street. Watling Street exits Milton Keynes as it crosses the Great Ouse.

On its route it crosses a number of streams and the Great Ouse on bridges, but these were probably fords in Roman times.

There were other Roman roads in the area. The Bletchley to Buckingham road is believed to be of at least Roman foundation.

"Viatores" is the name used by a number of scholars who published a book in 1964 which sought to identify possible Roman roads in the South East Midlands. Some of these roads are definitely Roman - but others are conjectures based upon known settlements, parish boundaries and previous archaeological finds. I'm not in a position to evaluate how much of work has been proven by later research - but the book is a useful starting point.

MKi Observatory used to have a Heritage Theme which showed the Viatores routes relative to the modern roads and paths. I have not been able to find it recently, but if anyone can provide a link - please share it with me. I do recall that one route crossed the southern end of Milton Keynes Central railway station, crossing Loughton towards Shenley Brook End near to the current route of Child's Way. The picture below shows the Viatores routes in the general area.

Route 175 heads for Irchester via Olney. following the course of the River Ouzel.

A copy of "Viatores" can be consulted in the main Milton Keynes library.

Tuesday 4 April 2017

The Bancroft Villa

It's nice to cycle up from our home in Furzton to Bancroft. The Redway follows the Loughton Brook, past some of the balancing lakes created to reduce flooding in that valley. Once past the concrete cows, the stream winds its way through Bancroft, with a footbridge linking to the western side - and the Roman Villa.

Fragments of Roman pottery were found by the stream fifty years ago. Major excavations took place between 1973 and 1978, directed by the Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit. Initially the site was backfilled and allowed to grass over. Then it was proposed in 1981 to create a full-size reconstruction of the villa at its most magnificent with a visitors centre and museum. Sadly these were the austerity 80s, and the ambitious plan was dropped. However further excavations were funded - covering an area of about 12,000 square metres.

The results of that excavation are set out in a two volume Monograph by R J Williams and R J Zeepat.

The earlier posts on Bronze Age and Iron Age Milton Keynes have already mentioned the settlement at Blue Bridge/Bancroft. It seems likely that the farmers there moved down the hill to the visible site of the villa. While the foundations of the main building are visible, the outbuildings lie buried underneath the open space between the roman remains and the pétanque piste to the north.

Where the Bronze and Iron Age settlement lay, a mausoleum was built. It continued in use, probably until the villa itself was abandoned in the fourth century CE (AD).

There are some excellent interpretation boards by the main villa building. The site was developed from the early years of the first century. We believe that the first farm (villa) on this site was constructed in the late first century. This was occupied until a fire destroyed mainly of the buildings in about 170 CE (AD). A large Roman style house was was built in the late third century - but there is no evidence that it was a farm. It was in the fourth century that the villa reached its full extent and glory. Clearly its inhabitants had become very prosperous.

The main residential building was decorated with mosaics. One of these is currently on display in the Milton Keynes shopping area (Centre:mk) - close to the toilets in Deer Walk (Entrance North 9). In front of the villa is a fishpond - and the room layout is explained on the interpretation boards and can be seen on the ground.

Fragments of Roman pottery were found by the stream fifty years ago. Major excavations took place between 1973 and 1978, directed by the Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit. Initially the site was backfilled and allowed to grass over. Then it was proposed in 1981 to create a full-size reconstruction of the villa at its most magnificent with a visitors centre and museum. Sadly these were the austerity 80s, and the ambitious plan was dropped. However further excavations were funded - covering an area of about 12,000 square metres.

The results of that excavation are set out in a two volume Monograph by R J Williams and R J Zeepat.

The earlier posts on Bronze Age and Iron Age Milton Keynes have already mentioned the settlement at Blue Bridge/Bancroft. It seems likely that the farmers there moved down the hill to the visible site of the villa. While the foundations of the main building are visible, the outbuildings lie buried underneath the open space between the roman remains and the pétanque piste to the north.

Where the Bronze and Iron Age settlement lay, a mausoleum was built. It continued in use, probably until the villa itself was abandoned in the fourth century CE (AD).

There are some excellent interpretation boards by the main villa building. The site was developed from the early years of the first century. We believe that the first farm (villa) on this site was constructed in the late first century. This was occupied until a fire destroyed mainly of the buildings in about 170 CE (AD). A large Roman style house was was built in the late third century - but there is no evidence that it was a farm. It was in the fourth century that the villa reached its full extent and glory. Clearly its inhabitants had become very prosperous.

The main residential building was decorated with mosaics. One of these is currently on display in the Milton Keynes shopping area (Centre:mk) - close to the toilets in Deer Walk (Entrance North 9). In front of the villa is a fishpond - and the room layout is explained on the interpretation boards and can be seen on the ground.

Labels:

Bancroft,

Bancroft Roman Villa,

Blue Bridge,

Bob Zeepvat,

Centre:MK,

Furzton,

Mausoleum,

Milton Keynes,

R J Williams,

Roman Britain,

Roman Villas.

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Tuesday 14 March 2017

Magiovinium

Watling Street crosses the River Ouzel close to Dobbies Garden Centre and the Bletchley Rugby Club (Manor Fields). Along the Roman road was a small town with buildings, (possibly some were shops) and a cemetery outside the defences of a bank and ditch. This is on a spur of land which gently slopes down to the Ouzel.

There have been a number of small excavations - starting in 1911 by Bradbook and Berry. In 1964 there were excavations of a bathing station, and a number in the 1970s to 1990s associated with the roadbuilding in the area.

(see for example the reports on the Little Brickhill by-pass, 1989-90 (link here) or the excavations that preceded the construction of the garden centre (link here))

A Roman coin manufacturing site was discovered in 1990, beneath the line of Galley Lane (the A4146), adjacent to a mid first century fort. Those coins are now on show in Room 49 (Roman Britain) in the British Museum. Two separate groups of coins were found, one set were fourth-century bronzes and the other were second century denarii.

The fort, a double-ditched rectangular enclosure, is likely to have build during the reign of Nero, and abandoned within 30 years. It is situated in the field which is bordered by Watling Street and Galley Lane (A4146)

There have been a number of small excavations - starting in 1911 by Bradbook and Berry. In 1964 there were excavations of a bathing station, and a number in the 1970s to 1990s associated with the roadbuilding in the area.

(see for example the reports on the Little Brickhill by-pass, 1989-90 (link here) or the excavations that preceded the construction of the garden centre (link here))

A Roman coin manufacturing site was discovered in 1990, beneath the line of Galley Lane (the A4146), adjacent to a mid first century fort. Those coins are now on show in Room 49 (Roman Britain) in the British Museum. Two separate groups of coins were found, one set were fourth-century bronzes and the other were second century denarii.

The fort, a double-ditched rectangular enclosure, is likely to have build during the reign of Nero, and abandoned within 30 years. It is situated in the field which is bordered by Watling Street and Galley Lane (A4146)

Labels:

Galley Lane,

Magiovinium,

Ouzel

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Saturday 11 March 2017

Roman Milton Keynes

Watling Street (though the Romans did not call it this), is the most obvious sign of the Roman presence in Milton Keynes. It enters Milton Keynes at the large island at the south of the A5 trunk route and is still in use through Fenny Stratford; closely passing the Tesco in Bletchley and as 'Denbigh Road,, parallel to Bletcham Way to the start of the V4. This modern road follows the original route (except to avoid Loughton (where the London Road follows Watling Street) and then along the High Street in Stony Stratford.

The Roman villa at Bancroft is also well known, but is not the only villa found in the area. A map in Bob Zeepvat's "Roman Milton Keynes" identifies villas in Holne Chase, Sherwood Drive (both Bletchley), Dovecote Farm in Shenley Brook End, Wymbush, Stantonbury and Stanton Low. He also notes that a site in Walton could be a villa and that the Ouse valley "is also particularly well endowed with villas, which occur at intervals of 2-3 kilometres along its north side." The term means farm - and some villas are really a collection of buildings dominated by a place of residence. The book on Bancroft shows that the extent of buildings covered most of the land between the open remains of the villa and the car par and the pétanque pitch. Wymbush's villa included a stone house and outbuildings including a barn. The picture above was taken at the British Museum and is of coins found near Watling Street as it enters Magiovinium (the Roman town mow within Milton Keynes).

Detailed lists of sites and findings are listed in Roman Milton Keynes: Excavations & Fieldwork 1971 - 82 edited by Dennis C Mynard.

An interesting book was published by the Museum of London Archaeology Service called "Becoming Roman". It traces the development from the late iron age to the end of the Roman period at Monkston.

All these publications are available in the Milton Keynes Libraries. The Main library in Silbury Boulevard has an excellent local studies sections sited within the Reference Section (though some can be borrowed).

There's a good interactive resource available at http://www.mkheritage.co.uk/mkm/mkarchaeology/Web%20pages/roman1.html

The Roman villa at Bancroft is also well known, but is not the only villa found in the area. A map in Bob Zeepvat's "Roman Milton Keynes" identifies villas in Holne Chase, Sherwood Drive (both Bletchley), Dovecote Farm in Shenley Brook End, Wymbush, Stantonbury and Stanton Low. He also notes that a site in Walton could be a villa and that the Ouse valley "is also particularly well endowed with villas, which occur at intervals of 2-3 kilometres along its north side." The term means farm - and some villas are really a collection of buildings dominated by a place of residence. The book on Bancroft shows that the extent of buildings covered most of the land between the open remains of the villa and the car par and the pétanque pitch. Wymbush's villa included a stone house and outbuildings including a barn. The picture above was taken at the British Museum and is of coins found near Watling Street as it enters Magiovinium (the Roman town mow within Milton Keynes).

Detailed lists of sites and findings are listed in Roman Milton Keynes: Excavations & Fieldwork 1971 - 82 edited by Dennis C Mynard.

An interesting book was published by the Museum of London Archaeology Service called "Becoming Roman". It traces the development from the late iron age to the end of the Roman period at Monkston.

All these publications are available in the Milton Keynes Libraries. The Main library in Silbury Boulevard has an excellent local studies sections sited within the Reference Section (though some can be borrowed).

There's a good interactive resource available at http://www.mkheritage.co.uk/mkm/mkarchaeology/Web%20pages/roman1.html

Labels:

Bancroft,

Bletchley,

Bob Zeepvat,

British Museum,

D C Mynard,

Denbigh,

Fenny Stratford,

Magiovinium,

Monkston,

Shenley Brook End,

Stanton Low,

Stantonbury,

Stony Stratford,

V4,

Walton,

Watling Street,

Wymbush

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Tuesday 7 March 2017

The Iron Age in Milton Keynes

I live in Furzton - a modern estate (with a beautiful lake - itself constructed in recent times). Yet I live very close to the site of a settlement which was inhabited during Iron Age times. So do many other people living across Milton Keynes. The archaeologists have found lots of evidence of Iron Age people across the city.

The Iron Age covers the period from around 800 BCE until the Roman invasion of 43 CE (AD). Of course the transitions between the Bronze Age prior to the Iron Age, and the Roman era following it were more gradual than sudden.

There were two settlements in Furzton. The first (probably) was close to the stream - close to where Loughton Brook becomes the Lake. The longer term settlement was just off Dulverton Drive, about 400 metres from the stream side site - and this was excavated in 1987 and 1988. [Full details can be found in the South Midlands Archaeology Journal 1986, 1987 & 1988 - available to download here] This was probably a stockade for animals, with some evidence of human settlement. The weather & the resultant water within the clay made, by all accounts, for a difficult excavation.

Was this an offshoot of a tribal sub-capital at Danesborough? or an unconnected development? Danesborough is scheduled as an Ancient Monument because it is thought to be of national importance. It has survived well and is a good example of an Early Iron Age fort. It was excavated in 1924. The shape can be described as roughly oval or rectangular with rounded corners. It would have given an extensive view northwards towards Newport Pagnell and Olney - and most of the modern city of Milton Keynes. The local tribe were the Catuvellauni, whose tribal capital was just outside Wheathampstead (which I hope to be writing a post about shortly) and then what is now St Albans.

We don't know whether Danesborough was merely a defensive position or a local centre which was to be eclipsed by the Roman town of Magiovinium.

The settlement at Blue Bridge from the Bronze age seemed to have been in continuous use through the Iron Age.

Pennyland was also home to an Iron Age Settlement. This is described in "An Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire"

and in greater detail in "Pennyland & Hartigans" (which also identifies iron age settlements in Hartigans gravel pit (in the area between Little Woolstone and Milton Keynes Village) Woughton, Wavendon Gate, Caldecotte and Westbury by Shenley)

A 2005 excavation in Tattenhoe Park also uncovered evidence of a settlement there. That report can be loaded from here.

Just outside Milton Keynes, in Little Horwood parish, the "Whaddon Chase hoard" was found in 1849, containing coins from the period 55-45 BCE.

The Iron Age covers the period from around 800 BCE until the Roman invasion of 43 CE (AD). Of course the transitions between the Bronze Age prior to the Iron Age, and the Roman era following it were more gradual than sudden.

There were two settlements in Furzton. The first (probably) was close to the stream - close to where Loughton Brook becomes the Lake. The longer term settlement was just off Dulverton Drive, about 400 metres from the stream side site - and this was excavated in 1987 and 1988. [Full details can be found in the South Midlands Archaeology Journal 1986, 1987 & 1988 - available to download here] This was probably a stockade for animals, with some evidence of human settlement. The weather & the resultant water within the clay made, by all accounts, for a difficult excavation.

Was this an offshoot of a tribal sub-capital at Danesborough? or an unconnected development? Danesborough is scheduled as an Ancient Monument because it is thought to be of national importance. It has survived well and is a good example of an Early Iron Age fort. It was excavated in 1924. The shape can be described as roughly oval or rectangular with rounded corners. It would have given an extensive view northwards towards Newport Pagnell and Olney - and most of the modern city of Milton Keynes. The local tribe were the Catuvellauni, whose tribal capital was just outside Wheathampstead (which I hope to be writing a post about shortly) and then what is now St Albans.

We don't know whether Danesborough was merely a defensive position or a local centre which was to be eclipsed by the Roman town of Magiovinium.

The settlement at Blue Bridge from the Bronze age seemed to have been in continuous use through the Iron Age.

Pennyland was also home to an Iron Age Settlement. This is described in "An Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire"

and in greater detail in "Pennyland & Hartigans" (which also identifies iron age settlements in Hartigans gravel pit (in the area between Little Woolstone and Milton Keynes Village) Woughton, Wavendon Gate, Caldecotte and Westbury by Shenley)

A 2005 excavation in Tattenhoe Park also uncovered evidence of a settlement there. That report can be loaded from here.

Just outside Milton Keynes, in Little Horwood parish, the "Whaddon Chase hoard" was found in 1849, containing coins from the period 55-45 BCE.

Labels:

Bancroft,

Blue Bridge,

Caldecotte,

Daneborough,

Furzton,

Iron Age,

Little Horwood,

Little Woolstone,

Magiovinium,

Milton Keynes village,

Pennyland,

Wavendon Gate,

Westbury,

Whaddon Chase hoard,

Woughton

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Saturday 4 March 2017

Milton Keynes' Bronze Age

The Bronze Age roughly covers the period 2300 BCE until 600 BCE. In reality these dividing lines are not as clear cut as we sometimes imagine. It is the introduction of metalworking in bronze (and also copper and gold) which defines this period - until iron becomes the major type of metal being worked. Another characteristic of this period was a distinctive style of burial involving decorated pottery (giving rise to the name 'beaker culture).

The evidence of Bronze Age settlement has largely come from excavation of ring ditches in the Ouse and Ouzel valleys. These are associated with burial mounds (Round barrow). The most significant finds were at Warren Farm (Wolverton Mill) - which may be the oldest; the nearby Little Pond Ground, Oakgrove and Cotton Valley (between Willen Lake North and M1 Junction 14).

There's an excellent piece about the settlement at Blue Bridge/Bancroft accessible at http://www.mkheritage.co.uk/mkm/mkarchaeology/Web%20pages/Bronze%20Age.html. The pottery is of bronze age type, but the buildings are closer to Iron Age types.

A number of Bronze Age artefacts have also been found in Stony Stratford (a socketed axe): Shenley (an urn and an arrowhead) and other sites around the city.

Near Newport Pagnell (Gayhurst Quarry) an early Bronze Age cemetery has been excavated. It had seven round barrows. At the centre of the largest barrow was a massive grave pit which showed a sequence of five successive burials from around 2000 BCE, while the six surrounding ones were 100 and 600 years later. The Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire says "What made this barrow remarkable was a deposit of cattle bones, perhaps the remains of 300 animals...The overall scale of the bone deposits provides as vivid an indicator of the wealth of the community that could afford to make this exceptional statement as the deposition of any number of artefacts. It illustrates the central importance of both cattle and ritual sacrifice to early Bronze Age communities"

The evidence of Bronze Age settlement has largely come from excavation of ring ditches in the Ouse and Ouzel valleys. These are associated with burial mounds (Round barrow). The most significant finds were at Warren Farm (Wolverton Mill) - which may be the oldest; the nearby Little Pond Ground, Oakgrove and Cotton Valley (between Willen Lake North and M1 Junction 14).

There's an excellent piece about the settlement at Blue Bridge/Bancroft accessible at http://www.mkheritage.co.uk/mkm/mkarchaeology/Web%20pages/Bronze%20Age.html. The pottery is of bronze age type, but the buildings are closer to Iron Age types.

A number of Bronze Age artefacts have also been found in Stony Stratford (a socketed axe): Shenley (an urn and an arrowhead) and other sites around the city.

Near Newport Pagnell (Gayhurst Quarry) an early Bronze Age cemetery has been excavated. It had seven round barrows. At the centre of the largest barrow was a massive grave pit which showed a sequence of five successive burials from around 2000 BCE, while the six surrounding ones were 100 and 600 years later. The Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire says "What made this barrow remarkable was a deposit of cattle bones, perhaps the remains of 300 animals...The overall scale of the bone deposits provides as vivid an indicator of the wealth of the community that could afford to make this exceptional statement as the deposition of any number of artefacts. It illustrates the central importance of both cattle and ritual sacrifice to early Bronze Age communities"

The British Museum has the "Milton Keynes Hoard", an incredible hoard of Bronze Age gold found in 2000 in a field near Monkston. It has been described as "one of the biggest concentrations of Bronze Age gold known from Great Britain". A hoard of weapons was found on what became the County Arms Hotel in New Bradwell.

Labels:

Bancroft,

Blue Bridge,

British Museum,

Bronze Age,

Cotton Valley,

Gayhurst,

Milton Keynes,

Monkston,

New Bradwell,

Newport Pagnell,

Oakgrove,

Shenley,

Stoney Stratford,

Warren Farm,

Wolverton Mill

Location:

Milton Keynes, UK

Wednesday 1 March 2017

The Stone Age in Milton Keynes.

At school we were told about the Stone Age. (To a young mind an 'age' might seem equivalent to any other 'age' - but the Tudor Age lasted 118 years. The Stone Age around 700,000 years) - There's an excellent account of the different periods within the 'Stone Age' in "An illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire" - edited by Michael Farley. The Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) covers most of the period - and includes time when ice covered Milton Keynes. The Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) covers the period 9000 to 4000 BCE, and the Neolithic (New Stone Age) can be divided into the Earlier Neolithic 4000 BCE - 3250 BCE and the Later Neolithic 3250 BCE - 2300 BCE.

We don't really know much about human activity in the Milton Keynes area during the Palaeolithic period. Several flint hand-axes have been found in gravel pits in the Bletchley area, and flint tools from around 12,000 BCE were found in a quarry at Manor Farm, Wolverton - but as R J Williams wrote - " Unfortunately there is no correlation between the distribution of palaeolithic artefacts and the faunal remains in the area, as all have resulted from chance discoveries, so it has not been possible to identify any pattern of activity for this period."

Significant quantities of Mesolithic flints have been found in the valley's of the three main rivers (see post from 21st February) - the Great Ouse, the Ouzel and Loughton Brook, with concentrations at Bancroft, Little Woolstone and what is now Caldecotte Lake. Mesolithic axes have been found a bit further away from the River Ouzel at Walton and Pennyland, which Williams suggests, " may indicate Mesolithic penetration into the woodland and perhaps the beginnings of woodland clearance on the heavier clay soils away from the river rallies."

With more settled lifestyles coming with the Neolithic age - we have greater evidence of people living permanently in the Milton Keynes areas. What is believed to be a neolithic Cursus was revealed in an extension of the quarry at Manor Farm, Wolverton.

Before the Roman villa at Bancroft was built, there was neolithic activity on Blue Bridge. At the very end of the period Stacey's Farm area (now Milton Keynes Museum) saw some farming. Other settlements have been identified at Heelands (around 2500 BC) and Secklow

We don't really know much about human activity in the Milton Keynes area during the Palaeolithic period. Several flint hand-axes have been found in gravel pits in the Bletchley area, and flint tools from around 12,000 BCE were found in a quarry at Manor Farm, Wolverton - but as R J Williams wrote - " Unfortunately there is no correlation between the distribution of palaeolithic artefacts and the faunal remains in the area, as all have resulted from chance discoveries, so it has not been possible to identify any pattern of activity for this period."

Significant quantities of Mesolithic flints have been found in the valley's of the three main rivers (see post from 21st February) - the Great Ouse, the Ouzel and Loughton Brook, with concentrations at Bancroft, Little Woolstone and what is now Caldecotte Lake. Mesolithic axes have been found a bit further away from the River Ouzel at Walton and Pennyland, which Williams suggests, " may indicate Mesolithic penetration into the woodland and perhaps the beginnings of woodland clearance on the heavier clay soils away from the river rallies."

With more settled lifestyles coming with the Neolithic age - we have greater evidence of people living permanently in the Milton Keynes areas. What is believed to be a neolithic Cursus was revealed in an extension of the quarry at Manor Farm, Wolverton.

Before the Roman villa at Bancroft was built, there was neolithic activity on Blue Bridge. At the very end of the period Stacey's Farm area (now Milton Keynes Museum) saw some farming. Other settlements have been identified at Heelands (around 2500 BC) and Secklow

Labels:

Bancroft,

Bletchley,

Blue Bridge,

Heelands,

Mesolithic,

Milton Keynes,

Milton Keynes Museum,

Neolithic,

Palaeolithic,

Pennyland,

R J Williams,

Secklow,

Walton,

Wolverton

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Saturday 25 February 2017

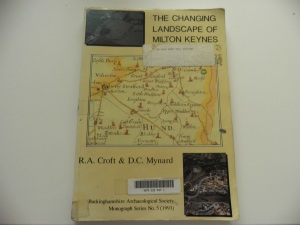

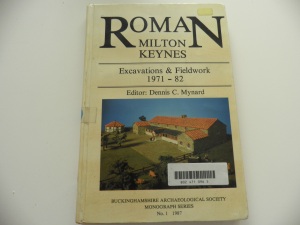

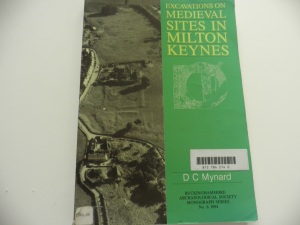

Books on Milton Keynes History

There are some excellent books to be found in Milton Keynes libraries (and not just the local studies section in the Central Library) – about the history of the city.

I’m currently borrowing (fear not, there are multiple copies) – three excellent books – which are aiding my research. I will be putting the results up on this blog.

The three books are

The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes – R A Croft and D C Mynard.This has a chapter by R J Zeepvat on the geology and topography of this area – an essential for understanding our city’s past and present; Descriptions of the area at different periods. [Prehistoric; Roman; Saxon; Medieval and Post-Medieval]; a chapter by M Gelling on place-names of the Milton Keynes area. It concludes with a series of parish essays – focusing on discoveries made in the old parishes of our city.

Roman Milton Keynes: Excavations & Fieldwork 1971-82 – edited by Dennis C Mynard. It has some excellent maps; drawings and lists of finds. There are also a set of photographs.

Excavations on Medieval Sites in Milton Keynes – also by Dennis Mynard in the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society Monograph Series. This too has some excellent diagrams & drawings; photographs and descriptions of the major sites.

I have my own copies of two excellent books – R J (Bob) Zeepvat’s “Roman Milton Keynes” which has chapters on Iron Age Background; The Roman Occupation; Roman Government; Towns; Communications; Countryside; Villas; Trade & Industry; Religion and Burial – and Further Reading.

and “An illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire” edited by Michael Farley – which describes the area and puts it into a wider context.

Tuesday 21 February 2017

Milton Keynes History

Last month the city of Milton Keynes celebrated its 50th birthday - but the area has much of historical interest. It is overlooked by the iron-age fort of Danesborough, includes the Roman settlement of Magiovinium, a Roman villa, the historic Watling Street coaching town of Stony Stratford, Bletchley Park and transport routes from across the ages (Watling Street, Grand Union Canal, Railway, M1). It includes a number of ancient villages and the historic towns of Bletchley, Stony Stratford, Wolverton and Newport Pagnell.

In this and subsequent posts, I will share something of that history. There is an excellent map called "Milton Keynes Heritage". I believe that it may still be available from the Visitor Information Centre in Centre:MK [the huge indoor shopping centre]

I've always believed that to understand the history of an area, it is necessary to study its geography. Milton Keynes is built on a low plateau, crossed by three rivers.

The biggest river forms the Northern boundary of the city itself, then crosses through some of the rural parts and through the town of Newport Pagnell. The Great Ouse runs 143 miles from its sources in Northamptonshire (near the village of Syresham), through Brackley, Buckingham, Milton Keynes, Olney, Bedford, St Neots, Huntingdon, St Ives and Kings Lynn before entering the Wash. The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum - which settled the border between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and Danelaw ran along the Great Ouse between Stony Stratford and Bedford.

The second river is the Ouzel (also known elsewhere and in other eras as the Lovat). It rises not far from Whipsnade Zoo - and flows through Leighton Buzzard and through the city close to the site of Magiovinium; past the Open University, meeting the Great Ouse in Newport Pagnell.

The third 'river' is a brook - but it has carved out a pleasant valley which is partly used by the railway. Loughton Brook rises a little outside the City to its south west. It flows through the estates of Tattenhoe Park, Tattenhoe, Emerson Valley, and Furzton - where it feeds Furzton Lake, past the Milton Keynes (National) Bowl, Knowlhill (where the Teardrop lakes are), Loughton, past Bradwell Abbey and close to the Roman Villa in Bancroft, eventually meeting the Great Ouse in New Bradwell.

In this and subsequent posts, I will share something of that history. There is an excellent map called "Milton Keynes Heritage". I believe that it may still be available from the Visitor Information Centre in Centre:MK [the huge indoor shopping centre]

I've always believed that to understand the history of an area, it is necessary to study its geography. Milton Keynes is built on a low plateau, crossed by three rivers.

The biggest river forms the Northern boundary of the city itself, then crosses through some of the rural parts and through the town of Newport Pagnell. The Great Ouse runs 143 miles from its sources in Northamptonshire (near the village of Syresham), through Brackley, Buckingham, Milton Keynes, Olney, Bedford, St Neots, Huntingdon, St Ives and Kings Lynn before entering the Wash. The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum - which settled the border between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and Danelaw ran along the Great Ouse between Stony Stratford and Bedford.

The second river is the Ouzel (also known elsewhere and in other eras as the Lovat). It rises not far from Whipsnade Zoo - and flows through Leighton Buzzard and through the city close to the site of Magiovinium; past the Open University, meeting the Great Ouse in Newport Pagnell.

The third 'river' is a brook - but it has carved out a pleasant valley which is partly used by the railway. Loughton Brook rises a little outside the City to its south west. It flows through the estates of Tattenhoe Park, Tattenhoe, Emerson Valley, and Furzton - where it feeds Furzton Lake, past the Milton Keynes (National) Bowl, Knowlhill (where the Teardrop lakes are), Loughton, past Bradwell Abbey and close to the Roman Villa in Bancroft, eventually meeting the Great Ouse in New Bradwell.

Labels:

Bancroft Roman Villa,

Bletchley,

Bletchley Park,

Danelaw,

Great Ouse,

Loughton Brook,

Magiovinium,

Milton Keynes,

Milton Keynes Visitor Information Centre,

Newport Pagnell,

Ouzel,

Stony Stratford,

Wolverton

Location:

Milton Keynes MK4, UK

Saturday 18 February 2017

Gloucester Cathedral

If you've watched the Harry Potter films, you might recognise the cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral. But it has played an important role in history long before that film series was conceived.

In 1085 William the Conqueror, at a meeting in Gloucester of his Great Council, commissioned the Doomsday Book. Some believe that the cathedral (or at least an earlier version of it, as a monastery) was the venue for that meeting.

Edward II, is buried in the Cathedral. He had been deposed and was being held at the nearby Berkeley Castle. His very convenient death is regarded by some as a murder. Many visitors have come to see his tomb, included the similarly ill-fated Richard II in 1378.

[George Marchant, who I met while visiting the cathedral, has written a short book called "Edward II in Gloucestershire", available in the Cathedral ]

The Cathedral was ancient at the time of those events. It was first established as a religious institution in the Seventh Century. by Osric, King of the Hwicce tribe (It is also claimed that he established what is today Bath Abbey). It became a Benedictine monastery in the early 11th Century.

It is a very nice cathedral to visit - in fact I made two visits while we were in this ancient Roman city last year.

Thursday 16 February 2017

The Rathaus, Hamburg

When I visited Hamburg for the first time, I was with a group of young political activists - visiting and staying with members of our sister party in Germany. The most unoriginal joke that was repeated on that trip concerned the name of the building in the picture. The Rathaus (Rat - Advisory Assembly, Parliament - as in Bundesrat) is the city hall - so the joke was about a house for rats (politicians).

It is a beautiful building - and I have many photographs of it. I sadly didn't have time to tour it on last July's visit - but next time!

Outside is the Rathausmarkt. Our visit coincided with an outdoor film festival. While waiting for the late night film to start, music was played through the loudspeakers. I really enjoyed the selection of French music that played. There were food and drink stalls around the square - selling food from the various traditions within Europe. The audience was also made up of people from many nations. Less than two decades before I was born, bombs brought by aircraft built in the region of my birth had been targeted on this city. Small plaques on the streets of Hamburg commemorate the people who had once lived there - but were taken away to concentration camps, from which many never returned. A moving statue outside the Bahnhof Dammtor recalls the Kindertransport - which brought many refugee children to Britain in the months preceding the outbreak of World War II. It was a timely reminder of how much had been achieved in the 20th Century after evil had visited our continent. A reminder of why we mustn't let history repeat itself.

Tuesday 14 February 2017

Hamburg Part 3

This is the model of medieval Hamburg - a densely populated which had become of the world's important trading centre. In 1381 Hamburg became part of the Hanseatic League. This trade alliance dominated trade in the Baltic and North Seas. The word 'Hansa' comes from the Middle Low German word for 'convoy'. The German airline 'Lufthansa' incorporates the word. (air convoy).

The Hanseatic League features in a book about the history of the North Sea.

During my visit I took a couple of cruises along the Elbe - one in the evening, with a meal with delegates from the conference my wife was attending, and the other during the day. I also used the U-bahn to get around the city and see some of the other sites. I look forward to returning to Hamburg - with not quite as long a gap as previously. [I had stopped in Hamburg for a very short stay back in 1978]. There is so much to see - and it is a very pleasant city.

Saturday 11 February 2017

Hamburg Part 2

My last post showed a photograph of the model of the earliest fortifications of Hamburg -

this is a photograph of the Hammaburg in all its glory.